There are different ways of managing forests. Clearcutting, with its characteristic open areas, is the most common in Sweden – but there are also other methods, known collectively as continuous cover forestry (CCF). What is best for growth, climate and biodiversity?

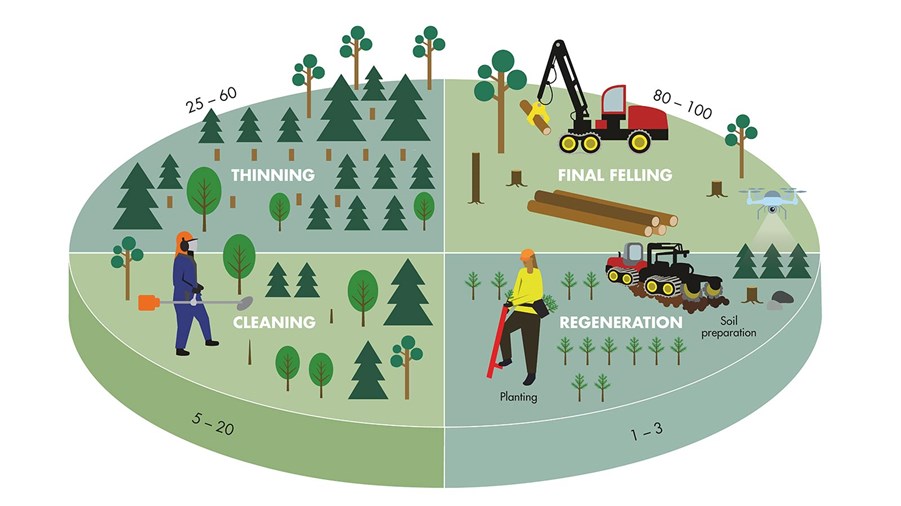

Clearcutting has long been the dominant method of Swedish forestry. It is an efficient method based on a cyclical process from planting to harvesting. Almost all trees in a given area are harvested at the same time and new ones are planted. Recently, however, there has been increasing interest in what is usually referred to as CCF methods.

Professor Tomas Lundmark, who works in the Department of Forest Ecology and Management at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), has followed forestry research since the 1980s.

“The choice of method depends on what you want to achieve. When it comes to timber production, clearcutting is more efficient than CCF methods, yielding an average of 15–20% more raw material per hectare. In addition, harvesting costs are about 20% lower than selective dimension cutting, for example, because clearcutting takes place at one time and in one place, resulting in less transport over shorter distances.”

Have been in use for many years

The common principle of the different continuous cover methods is that the land is always covered with trees. In other words, harvesting does not create large treeless areas in the way that clearcutting does. CCF methods have been in use for many years, not least as a complement to clearcutting. But which method is best – and from what perspective? This question is being studied on several fronts.

In 2021, SLU launched a series of experiments in collaboration with a number of forestry companies, including Södra – an association of 50,000 private forest owners – to compare different forest management systems. To date, the number of scientific studies of this kind in southern Sweden has been limited.

“We want to provide sound advice to our members, based on science and proven experience. We’re currently investigating and comparing selective dimension cutting, patch cutting and shelterwood cutting. We are collecting experiences from forest owners and testing the methods ourselves in an experimental area consisting of spruce, pine and deciduous forest stratified by height, diameter and age. A fourth area, left untouched, is also included. In 2023, we’ve been training our forestry advisors in CCF methods so that they can always carry out their work in a professional manner, whatever method the forest owner chooses,” says Magnus Petersson, Director Södra Forestry Department.

Are CCF methods better for biodiversity than clearcutting?

“We’ll see what SLU’s research results suggest. If only large trees are removed and most of the forest is left in place, shady conditions will remain even after harvesting, which favours animals and plants that thrive in moist and dark conditions. If, on the other hand, we create large open areas by clearcutting and leave very few trees behind, the species that thrive on light and warmth do better. So the more different methods we use, the greater the biodiversity effect, but we don’t yet know what proportion is ideal,” says Petersson.

Which method is best from a climate perspective?

“The faster a forest grows, the more carbon is sequestered in the wood. The system that absorbs the most carbon over time therefore provides the greatest climate benefit.”

Lars Erik Levin has extensive personal experience of different methods. He has managed his family farm for more than 40 years and continues to practise CCF in some areas, just as his father did. Levin applies clearcutting practices on around 70% of the forest, while the rest is subject to selective dimension cutting.

“Both methods are needed, but they have different strengths. I try to think about what’s best for both nature and my wallet. Clearcutting involves a lot of thinning, and the trees grow faster. From a production perspective, this is good because the volume of wood per hectare increases over time. And the more wood we can produce, the more carbon dioxide we can store.”

A selectively cut forest comprises a mixture of trees of all sizes, from small one-year-old seedlings to large mature trees. In the darker forest, the trees grow slowly, which means better quality timber. But switching to 100% CCF is not an option.

“With such a slow growth rate, it takes a long time to convert forest from clearcutting to

selective dimension cutting. If I decided to switch entirely to continuous cover, I’d have to start from scratch, and it would take up to a century,” says Levin.

Major impact on the Swedish economy

It takes 50–100 years to convert a forest from clearcutting to CCF. Professor Tomas Lundmark points out that such a conversion would have a major impact on the Swedish economy.

“During the conversion period, there would be a significant loss of growth and harvesting would be volatile. In the long term, growth would be lower and timber volumes would be drastically reduced.

From a climate perspective, a transition would boost the carbon sink effect in the short term, as harvesting is reduced. However, a reduced supply of forest products would risk increasing the use of fossil materials such as oil and cement.

“So overall, the climate benefit is less,” says Lundmark.

Would biodiversity benefit from such a transition?

“In the short term, a rapid transition to CCF is likely to have little effect, as it takes time for biotopes to adapt. Over the long term, changing the forest management system may result in some species benefiting more than today, while others that are dependent on open spaces and fires, for example, would instead be disadvantaged. Many studies show that clearcutting with increased nature conservation work has had positive effects on biodiversity,” says Tomas Lundmark, who continues:

“Since no single forest management system can benefit all species at the same time, using a variety of forest management practices would seem to be a better strategy. This could, for example, be based on clearcutting, but where the aim is to benefit species that require continuity or where there are social reasons to avoid clearcutting, it could be supplemented by CCF methods.”

CCF and clearcutting

With CCF, the ground is always covered with trees and regeneration is mainly natural. There are different types of CCF – for example, selective dimension cutting, patch cutting and shelterwood cutting.

With clearcutting, trees are about the same age and new seedlings are planted after harvesting. Clumps of retention trees, high stumps, dead wood and protective buffer zones are left to promote biodiversity.