Forests play a key role in efforts to achieve the climate goals. Growing trees absorb carbon dioxide, so it is important to ensure that forests grow more. But we must also seize this opportunity to phase out and replace fossil-intensive materials. This is how we achieve the greatest possible climate benefit, says researcher Rolf Björheden, who has studied the effects of recycling and substitution.

“Products that we use for a long time, such as sawnwood, and single-use materials, offer very tangible climate benefits. When we also recycle products again and again, this positive effect is multiplied,” Björheden says.

A major challenge in the green transition is the phasing out of fossil products. But there are alternatives and much of what we use in our daily lives –for example building materials, textiles and packaging – can be made from biogenic materials such as wood. Using wood fibre offers many advantages: it is fossil-free, renewable and as a product, it continues to store carbon during its lifetime.

Debate on the issue tends to make a distinction between what are called long-lived products, for example building materials, and short-lived products, single-use cups being a classic example.

But just how big a positive climate effect can a single-use cup have?

“I think we’ve paid far too little attention to the value of the short-lived products and their capacity to reduce the prevalence of fossil carbon. Only a small number of studies have been conducted into their climate impact, but it’s very important to understand how they contribute to climate benefit. My preliminary results suggest that short-lived products offer considerable climate benefit,” explains Björheden.

Björheden is a senior researcher at the Forestry Research Institute of Sweden (Skogforsk) and has made a preliminary calculation regarding the significance of short-lived forest-based products in substitution effects. He based his work on official statistics and published scientific research results.

Substitution is necessary

Björheden believes that using raw materials from forests to substitute – replace – fossil materials is the most important application forests have.

“Until now, there’s been too much focus on solving the climate crisis by storing carbon in forests. Many people talk about leaving forests untouched. But using forests purely as a glorified bin bag for fossil carbon is a short-term way of looking at this. Simply storing biomass does not generate the greatest climate benefit. We achieve the greatest climate benefit when we use biogenic products that reduce the use of fossil carbon.”

Björheden believes that anyone who ignores the substitution effect of short-lived renewable products risks shooting themselves in the foot.

“Short-lived bio-based products replace fossil alternatives. Based on available data, they contribute to a surprisingly high degree of increased climate benefit,” Björheden says.

Four times the climate benefit

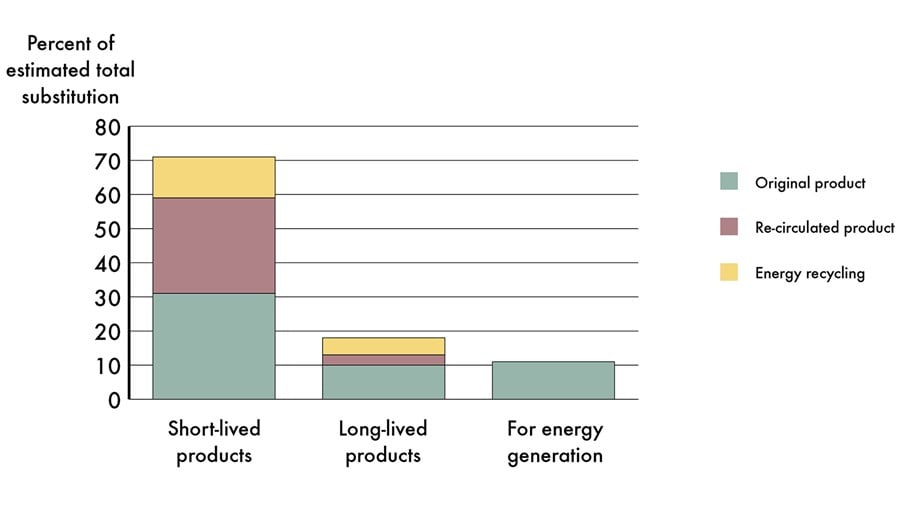

Björheden’s analysis assumes that 20 per cent of the wood in Sweden’s annual harvest is used for long-lived products with an average lifespan of 30 years. The lifespan of short-lived products, which correspond to 80 per cent of the total withdrawal, amounts to two years.

“When we take into account recycling rates, recirculation and energy recovery according to Swedish official statistics, substitution effects mean that short-lived forest products can prevent the emission of 50 per cent more fossil carbon per ‘invested carbon atom’ compared to long-lived products.”

“Long-lived products contribute to extended [carbon] storage, but short-lived products with high recycling rates can account for more than 80 per cent of substitution benefits. We already know that phasing out fossil materials is good for the climate, but the importance of recycling and circularity has not been as obvious,” says Björheden.

But using forests purely as a glorified bin bag for fossil carbon is a short-term way of looking at this. Simply storing biomass does not generate the greatest climate benefit. We achieve the greatest climate benefit when we use biogenic products that reduce the use of fossil carbon.”

But why is it so important to continue to manage forests to be able to use their raw materials to make products? Shouldn’t forests be left untouched for the sake of the climate?

“Severely limiting forestry makes it possible to continue using fossil coal. It’s a short-term solution. Stock growth in unused forests has positive effects to begin with, but after a relatively short period it results in lower overall growth. It is by maximising growth that forests bind the most carbon dioxide. The major climate benefits arise if we combine maximum growth with the use of forest products that prevent more fossil carbon from being added to the biosphere,” says Björheden, adding:

“Long-lived and short-lived products provide a very tangible climate benefit compared to only using forests as carbon sinks. When we also recycle products again and again, this positive effect is multiplied.”

If we reduce the supply of forest products and limit the forest sector, we create a very unfortunate situation with higher fossil emissions.

A new approach from the EU

Björheden highlights the importance of managing forests sustainably. Striking a balance between growth and harvesting is an important component in the concept of sustainability.

“Sweden can’t solve the climate crisis. Globally, the task is to gradually restore Europe’s and the world’s forests and develop sustainable forestry. Sweden can contribute to these efforts with knowledge and experience. In sustainable forestry, at least as many trees are grown as are cut down,” says Björheden and concludes:

“I can see signs that more people around Europe are beginning to understand the importance of forestry. I’m convinced that we’re now on the threshold of a new era of substitution, in which forest biomass increasingly replaces environmentally and climate-damaging fossil products.”

Research details

The analysis of the substitution effects of forest products is based on official statistics concerning which products are manufactured from wood harvested in Sweden and the substitution factors outlined in scientific literature. The climate effects of various products were then calculated using data on collection rates, material loss and recycling into new products or as energy.

Product lifetime plays a vital role in calculating ‘extended storage’, i.e., products’ carbon storage capacity. Short-lived products, (mainly paper and packaging materials), were assumed to have an average life of two years, while long-lived products, (such as timber and boards for building and construction), were estimated to have an average life of 30 years.

The analysis shows that in order to contribute to the greatest possible climate benefit, it is important that the short-lived products replace fossil materials, and that they are recycled or reused.